A favourite trope of dystopian plots is the present seen through the lens of the past. Cut to the closing scene of Planet of the Apes and Charlton Heston as astronaut George Taylor, having a “damn you all to hell” moment when confronted by the ruined remains of the Statue of Liberty.

In the freeze-frame moment this world has found itself in, there is every possibility that revisiting the present as an artefact of the past will become commonplace. The past, too, has suddenly thrust itself upon us as the new now. Queuing for rations, walking in the park with the family, learning to bake bread, grow greens, really talk to someone and so on – these once belonged to a previous time when apparently ‘life was simpler’.

The reality of plans put on indefinite hold is yet to be fully understood within the wider art world. Individual artists, faced with postponed exhibitions, will need to find a way forward that involves treating current work, destined for the market place, as compost for work yet to come. Some of this work, made at the time with such urgency and passion, may never be seen. Major exhibitions can sometimes be rescheduled if loan arrangements allow. But the phenomena of the exhibition interruptus is new and challenging territory, if only because the withdrawal method has always been a bit unreliable.

Since 26 March this has been the unfortunate status of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres. The exhibition, along with the Gallery, was forced to close until further notice, placing Monsters into a limbo of suspended animation. But, with South Australia’s suite of COVID-19 restrictions thawing a little earlier than expected, we have a chance to revisit curator Leigh Robb’s Monster Theatres, reawakened from their sleep.

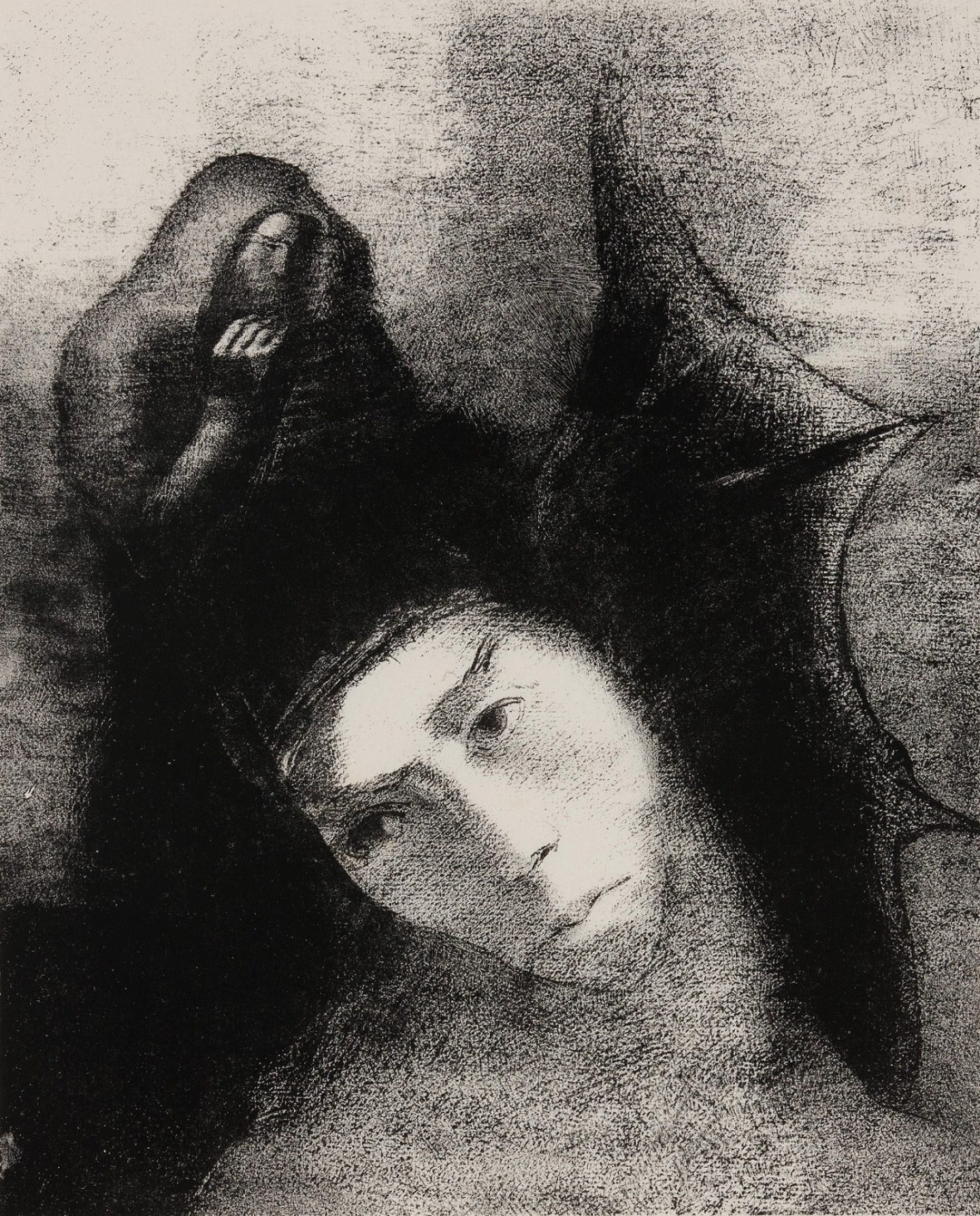

My starting point for engagement with Monsters is a work by Odilon Redon which is in Monsters’ companion exhibition, Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters – a terrific place to begin your Monster Theatres journey. This display echoes the Biennial’s exploration of contemporary monsters through the visualisation of monsters in European printmaking from the 15th to 19th century. Locking minds with intense images of suffering, terror and wonder created for communities that lived and breathed folklore and fabulous stories is an intense experience.

Odilon Redon, France, 1840 – 1916, Anthony: What is the point of all this? The Devil: There is no point!, plate 18 from The Temptation of St Anthony (third series), 1896, Paris; printed by Blanchard and August Clot, Paris; published by Ambroise Vollard, Paris, lithograph on paper; South Australian Government Grant 1973, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Odilon Redon, France, 1840 – 1916, Anthony: What is the point of all this? The Devil: There is no point!, plate 18 from The Temptation of St Anthony (third series), 1896, Paris; printed by Blanchard and August Clot, Paris; published by Ambroise Vollard, Paris, lithograph on paper; South Australian Government Grant 1973, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

If and/or when Monsters is open for business again, start your journey in Sleep of Reason. It only takes moments with Dürer’s menageries of horrors such as his mutant creatures, or Bruegel’s warnings of the perils of sinful behaviour, to appreciate that to be human, in any age, means facing fears of the unknown. The monstrous beasties, witches, spectres of death and devils that crowd these images can be dismissed as superstitions. But in the context of plagues, injustice and incessant wars that racked the Europe of a distant age, they had real reasons to live. An aspect of significance in the context of Monsters is the fact that in so many of these prints the skies are taken over by winged terrors, contrary to the usual arrangement, which has the heavens reserved for angels or a blue skies highway to Heaven. There is no escape.

In an object lesson for contemporary artists who believe that bigger is better, Redon’s 1896 print of St Anthony in conversation with the Devil claws its way into contemporary consciousness by virtue of its dramatic counterpoint of the Devil’s human face and the saint. Redon, interpreting Gustave Flaubert’s retelling of the temptation of St Anthony depicts the moment when the saint questions the Devil on the purpose of God. “What Is the Purpose of All This?” The Devil replies, “There Is No Purpose!” Sigmund Freud wrote of Flaubert’s text, “It calls up not only the great problems of knowledge, but the real riddles of life… [and] our perplexity in the mysteriousness that reigns everywhere.”

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Understudy by Abdul Abdullah, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Understudy by Abdul Abdullah, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

From Redon it may be possible to step into Abdul Abdullah’s Understudy. An unnervingly realistic Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, dressed in expensive sneakers and fashionable hoodie, sits expectantly, waiting for the curtain to part in a mock cabaret setting. It’s a hybrid worthy of any Middle Ages bestiary. As the title says,

“this hopeful monkey is an ‘extra’ waiting for the curtain to rise on opportunities that never come. It might be waiting for Godot or even God to appear and call it up onto the stage. Society, this tableau suggests, needs this arrangement, people and peoples on standby. “

There is, as Flaubert’s Devil advises, “no purpose” to this. Once entertained within the confines of the exhibition, this idea easily takes root. The monstrousness of systems, legacies, powerlessness, racism and so on cleaves this exhibition with the precision and power of an axe blade. Straight away, one is able to co-opt similar works. Megan Cope’s installation (Untitled), for example, calls out the ongoing destruction of Country (“the Colonial Beast” chewing “on the fat of the land”). This is one installation that delivers. Its initial resemblance to an abandoned mining site coalesces into a theatrical stage as the plaintive call of the curlew (the threatened ,yellow-eyed bush stone-curlew) becomes audible. How extraordinary that a small bird should be called upon to strike a note of warning into the hearts of listeners or that the dumbest of objects – even instruments of destruction (rock drills) – could be co-opted into a symphonic gesture of defiant beauty.

Terrifying beauty signifying nature’s claw back of agency in the Anthropocene informs Mark Valenzuela’s installations of mythical monsters both in the Art Gallery site and at the Botanic Gardens. The stairway descent in the Gallery takes the viewer into Valenzuela’s underworld (Once bitten, twice shy). This odd configuration resembles a shanty town of half-submerged tin shacks infested with effigies of gods and mythical creatures. The artist’s agenda of reinserting atavistic presences into a world on the edge of losing its inner humanity suggests that some monsters will always be with us in the form of consequences.

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Untitled (Death Song) by Megan Cope, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Untitled (Death Song) by Megan Cope, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Julia Robinson’s seductively dangerous Beatrice, at the Museum of Economic Botany (which will also reopen from the weekend of 5 June), acts like Valenzuela’s predatory flytrap in the Bicentennial Conservatory – invoking a sense of dread mingled with fatal attraction. Robinson is quite open about her capacity to create and live with such malevolent forms. “My monster is my imagination – it is ever-present and will not be subdued!”

Externalising and learning to live with our fears also seems to be the driving force behind a number of works in the exhibition. Judith Wright’s risky strategy of privileging shadows while revealing their commonplace sources (toys and found objects) pays off in her Tales of Enchantment. This immersive puppet play requires the viewer to momentarily revisit childhood experiences when shadows on the wall fired up the imagination. There is no moral here, no warning, just a reminder that storytelling is in our DNA. A similar strategy of manipulating a loose coalition of textiles and objects enables Mikala Dwyer’s installation (presciently described by Leigh Robb as “a space of quarantine”) in the Gallery vestibule to call upon the imagination to join the dots and see this invitation to be cheery for what it is.

So, is learning to live with, and even confront, fears one of the big takeaways from Monsters? I think it is, and it is manifest in a spirit of defiance that runs through the show. This is evident in Pierre Mukeba’s portraits of African men and women who are cast as resilient and strong in the face of civil war and atrocities.

Mike Parr’s calm recounting his daily experiences recorded in a diary sits disconcertingly at odds with his collage of performances which involved self- inflicted bleeding, burning and strangling. Brent Harris’ Grotesquerie, a series of 26 paintings made over an eight-year period, is a section torn from a personal diary of excavation of a troubled family relationship. It may help to know that the horned creature is the artist’s father and the yellow-haired woman is his mother. But these mesmerising images are universal in application and could be anyone’s – even yours – because they come very close to those elusive night-sweat images that invade the sleepless nights of many.

Yhonnie Scarce with her work In the Dead House, 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres

Yhonnie Scarce with her work In the Dead House, 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres

Aldo Iacobelli has used the theme to revisit a Naples childhood defined by hardship and some bitter memories. The artist has always found a way to traverse the hidden pathways between the gutter and the heavens. His trolley of potatoes represents not only the bite of hunger but a reminder of life, reduced by inequality and intolerance, to survival.

While rotating on the rack of his Reclining Stickman, Stelarc challenged conventional views of bio-cybernetics as ‘monstrous’ with characteristic laughter.

Defiance of the view that monstrous acts of colonial settlement are better forgotten in the interests of ‘moving forward’ defines Yhonnie Scarce’s installation, In the Dead House, at the Adelaide Botanic Gardens. The work responds to the fact that William Ramsay Smith, appointed in 1852 as City Coroner, conducted illicit dissection and removal of human remains under the guise of ‘medical research’. He was acknowledged as one of the most prolific colonial collectors of Aboriginal bones and soft tissue. The artist intends that this exhibition, consisting of ruptured glass objects based on traditional Australian bush vegetables “talks about the spirits that might be left behind in the space and telling their stories. This is about the horrific history and wanting to call these perpetrators out and making them accountable”.

Finish your season of Monster Theatres with a turn around Karla Dickens’ satirical cornucopia Dickensian Country Show – an installation that captures the bitter-sweet mood of Monsters’ collective take on things that we might need to be fearful of or treat as beacons to chart safe passage.

AGSA reopens Friday 5 June

5 June – 2 August 2020

2020 Adelaide Biennial:

Monster Theatres

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox