Tony Kearney: HEAT

The Banksia Tree Café, Port Adelaide

5 – 30 August

“Heat is not always the opposite of cool” – Tony Kearney

These images have been inspired, as the artist states, by a long-standing fascination with ‘intrinsically beautiful, well-designed and well-engineered products.’ Among these examples, collected and photographed by Kearney, are domestic heaters from the 1930s to the mid twentieth century. An appealing aesthetic feature, for the artist, is that they were designed to fit into Art Deco, Streamlined, Modernist and mid-century homes. They replaced the smoky fireplaces of a colonial to Depression-era past and (in wealthier homes) symbolised prosperity and modern taste.

Tony Kearney, Heat #5, 2020, Giclée print on cotton rag, 84h x 67w, Edition 1 of 5

Tony Kearney, Heat #5, 2020, Giclée print on cotton rag, 84h x 67w, Edition 1 of 5

These are no cheesy, mock-log fire items but true love children of the modern era with its embrace of new materials (such as chromed and painted steel, aluminium, Bakelite) and stream-lined minimalism. A spectacular example is a 1930s fan heater, manufactured by His Masters Voice (HMV) which looks so like a stack of. Walkman pods. For those who want to go further behind the scenes – Kearney’s foray into what he calls ‘machine-age archaeology’ has involved lots of even older-school technology – items set up on his kitchen table to catch natural early morning or dusk light, and shooting with a large format, 1950s (Linhof) camera (with a Dallmeyer 3C 1880s portrait brass lens).

Wow. To a photo/steam punk twitcher such descriptions are pure poetry. Somehow, in such company, that split cycle Panasonic unit, is never going to hold your gaze.

John Foubister, Gerry Wedd: Lost in Spaces

South Seas Trading, Port Elliot

8 – 30 August

New work by John Foubister (paintings) and Gerry Wedd (ceramics) always commands interest. Their respective practices are deeply studio-based which means that there is always something going on – a searching very often for fresh possibilities or a better way to express ideas that exist at the corner of the eye or in fragments of self-conversation. Wedd invited Foubister to join him on the basis that he has always been drawn to the painter’s approach to generating images. He identifies in this approach a ‘beguiling quality’ – a communicated by constantly reworking aesthetic aspects and solving technical challenges.

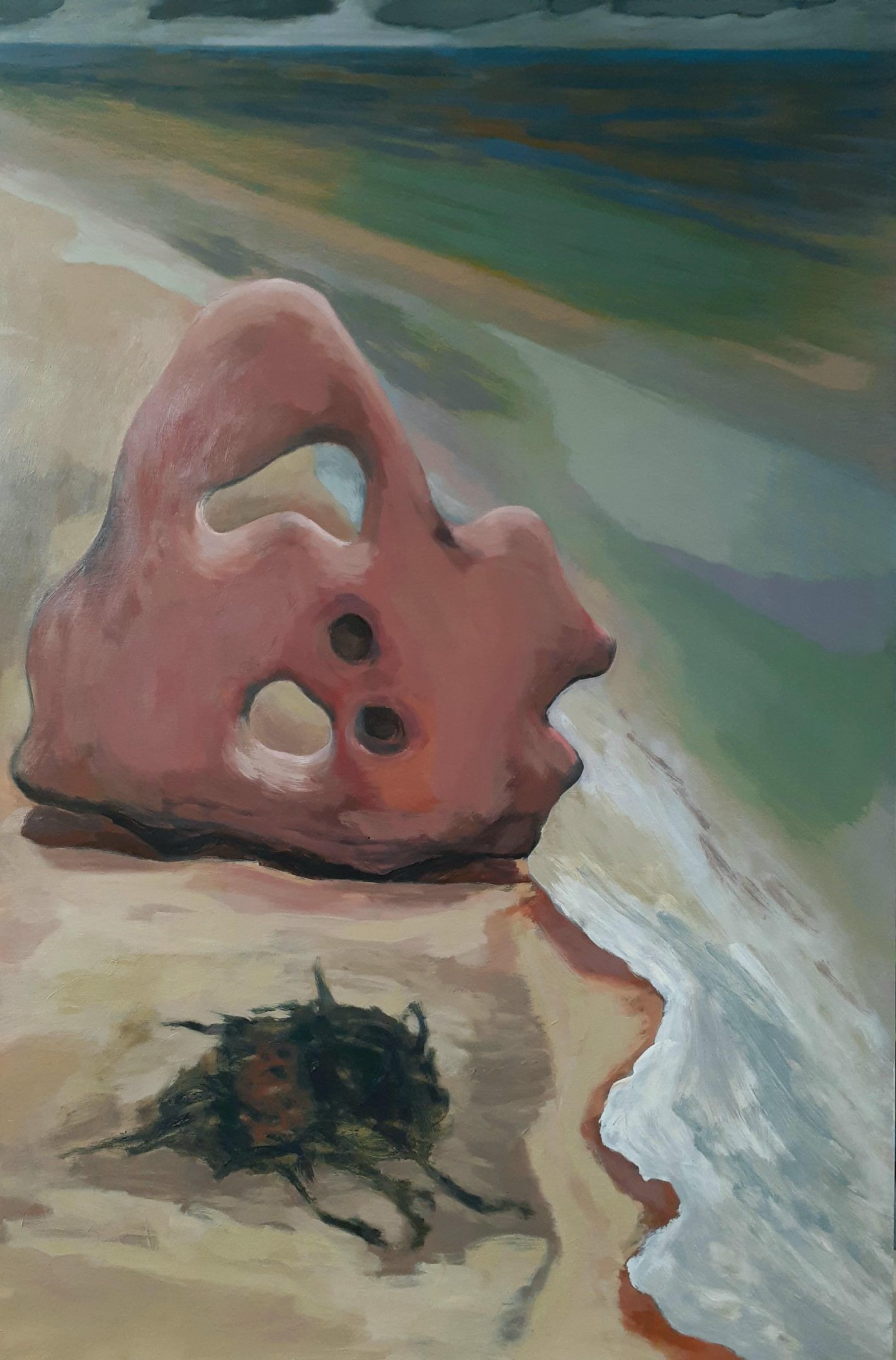

It is as much, Wedd suggests, an ‘unsolving’ process as much as a resolution of diverse factors. The artists’ imagery and forms have been inspired by the coastal area around Port Elliot where they both live and work. Wedd’s ceramic objects are characteristic of the artist’s very sophisticated ‘take it or leave it’ mode of avoiding over finessing and leaving the imprint of the thinking process communicated by such things as subtle asymmetries and free flowing illustration, as seen in his Hokusai wave meets Whitely whiplash vessel. Foubister has said that his practice in ‘one of discovery… I aspire to primarily maintain an attitude of searching, primarily for an understanding of the world.’

John Foubister, Sea stone and grass, 2020, 82 x 122 cm

John Foubister, Sea stone and grass, 2020, 82 x 122 cm

He admits to a compulsive approach to generating his images. Those in Lost in Spaces are clearly referencing shoreline subjects, but the push/pull exchanges between figuration and abstraction and between precise modelling and gestural brush strokes give these images the kind of dream-like qualities easily associated with mid-war surrealists, particularly Paul Nash, or, closer to home, Ken Whisson They are unapologetically heartfelt.

Morgan Allender: Soft Grass and Silence

Online exhibition

Last summer’s Adelaide Hills fires in December came close to destroying Morgan Allender and partner’s home. Morgan, her partner Justin, a cat and two dogs fled for their lives in the ute. The surrounding area was burnt out but the house, Allender’s studio and the surrounding garden were spared. The majority of trees, hedges and plants were unharmed apart from leaf scorch and ember burns. Shaken, like so many by the trauma, Allender found consolation in being able to get back to work. She talks of being able to pour onto her canvases her feelings about being spared, being alive and appreciating the cathartic effect of art making and observing nature re-healing. Most of the paintings in this (on-line exhibition) are large.

Morgan Allender, Soft Grass And Silence, 2020 oil on linen, 147 x 183cm

Morgan Allender, Soft Grass And Silence, 2020 oil on linen, 147 x 183cm

This marks a departure from previous, more intimated modes of work and the incorporation of larger areas of pure colour and free brushwork. Along with this is slightly less articulation of specific forms such as flowers and leaves. Allender describes these new paintings as ‘immersive studies of daylight, weather and foliage.’ The imagery is a combination of trees, hedges and flower-studded grasses observed from the studio window as well as a compendium of collective gardens of memory and experience. The artist intends that the large scale of these works will engender an immersive experience for the viewer, akin to her her own journey of reconnection with a paradise almost lost. Monet’s garden at Giverny (and related paintings) remains an inspiration but these celebratory images communicate an independent eye and spirit with just a hint of summers yet to come.

Ed Douglas: Duologue

Wendy Dixon-Whiley: Full Circle 1.0

Hahndorf Academy

31 July – 30 September

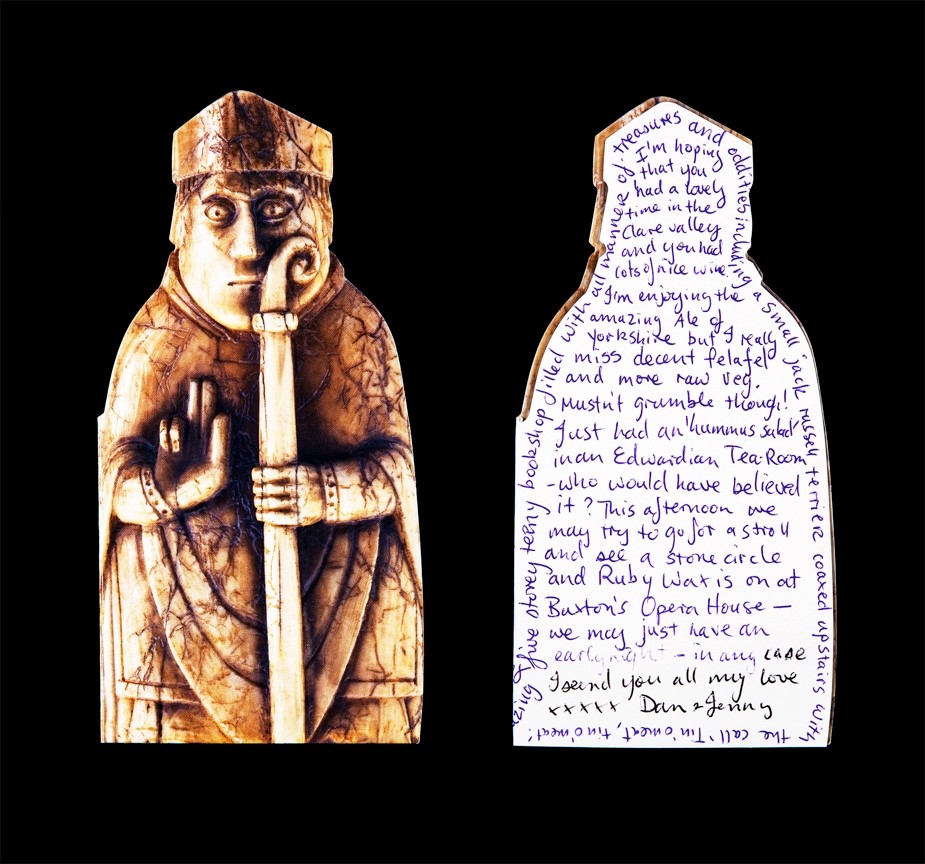

Significantly, Ed Douglas prefaces his insights into his current exhibition with a quote from author Julian Barnes. ‘You put together two things that have not been put together before and the world is changed.’ This simple idea has been the driving force behind so much modern, art, music, cinema and writing. René Magritte, who Douglas regards as one of the most intelligent of artists had it this way, ‘Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.’ Douglas and Magritte share a strategy designed to stimulate new ideas. It involves juxtaposing two things that would never be associated in ‘normal life’. Magritte famously tweaked this when his painting of a pipe was accompanied by the statement ‘This is not a pipe’ – thus highlighting the very arbitrary role of language in making sense of the world. Douglas, in this exhibition, has generally used the juxtaposition of two disparate objects, sourced from post cards, sites and studio archives to confront viewers with visual conundrums likely.

Examples are many. Aligning a coil of twine with a toilet roll (The Bizarre Tale of a Roll of Twine and a Roll of Toilet Paper) is one example which tips the viewer into a non-sequitor moment of wondering why these two items are occupying the same pictorial space. Another, (Dan’s Card: A Tale of Time & Travel sent from the UK to Australia 2019) does offer a clue in the form of a past card fragment containing a reference to ‘standing stones’ which aligns (sort of) with the image of a 12th century Viking chess piece opposite. Douglas sees a parallel in our ability to play with possible relationships between things and the manner in which we manage relationships with the people in our lives. All is flux. Each new relationship produces different perceptions and outcomes.

He says “That same ‘tug-at-identity’ that happens between two people also may occur between two objects placed in close proximity. Certain subjective narratives are suggested by these object-relationships. Some convey a poetic relationship, or a simple humour, while others may uncover an uncomfortable truth.” His intent appears to be to use the visual imperative of the photographic image to create improbable but beguiling binaries which demand some kind of resolution. And that resolution involves the use of the imagination. “I want people,” Douglas says, “to use their imaginations”. With this in mind consider that the real agenda of Douglas’ current practice is not the photography but the transaction this medium facilitates between the artist, the viewer and the wider world.

Ed Douglas, Dan’s Card: A Tale of Time & Travel, 2019, 1/6 (Scandinavian 12th-13th century ivory bishop chess-piece found on the island of Lewis in 1831, National Museum of Scotland) Framed artwork: 97cm x103cm

Ed Douglas, Dan’s Card: A Tale of Time & Travel, 2019, 1/6 (Scandinavian 12th-13th century ivory bishop chess-piece found on the island of Lewis in 1831, National Museum of Scotland) Framed artwork: 97cm x103cm

Wendy Dixon-Whiley: Full Circle 1.0

Wendy Dixon-Whiley’s drawings are the resolution of a body of work commenced at a 2019 Arts Residency in Tuscany. This residency allowed the artist to continue research of Dante Alighieri’s ‘Inferno’. The artist chose to focus on bodily representations of each sin depicted with the poem. The figurative style is appropriately characterised by fragmentation, coalescence, distortion and the grotesque. Dixon-Whiley has done enough homework of traditional canonical pronouncements on the sins of the flesh to see the funny side of efforts to police inner desires. The outcome is a high energy, funky mode of cartooning readily deployable as street art or book/screen illustration/animation.

Head to our Adelaide Review Event Guide to find out what else is happening around the city

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox