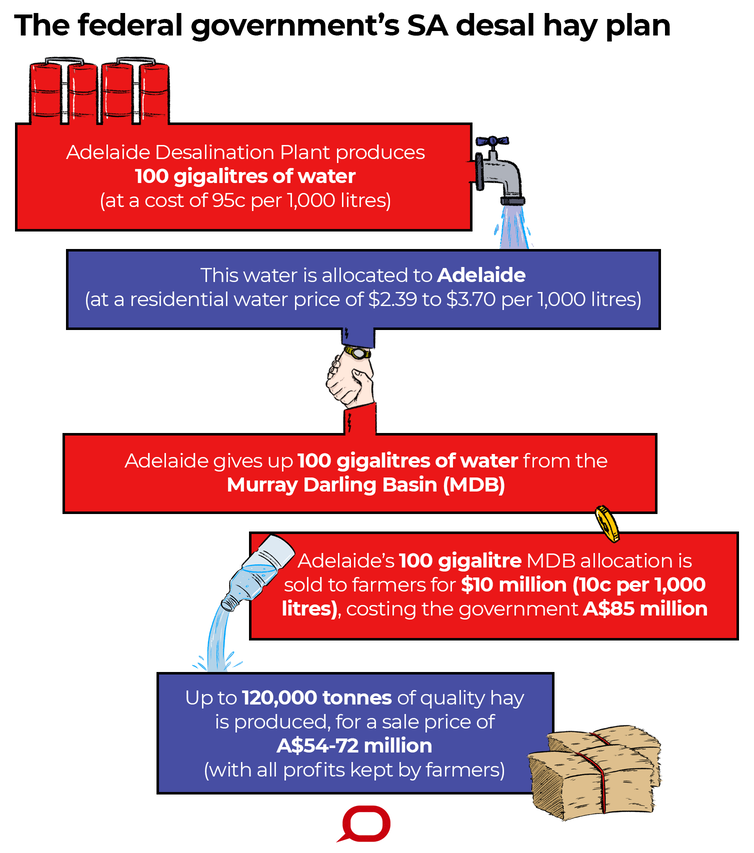

It involves the federal government paying the South Australian government up to A$100 million to produce more water for Adelaide using the little-used desalination plant.

The plant was commissioned in 2007 at the height of the millennium drought. It can produce up to 100 gigalitres of water a year – enough to fill 40,000 olympic sized swimming pools. But has been used sparingly, operating at its minimum mode of

8 gigalitres a year, because of the expense of turning seawater into freshwater.

Adelaide has continued to mostly draw water from local reservoirs and the River Murray, which on average has supplied about half the city’s water (sometimes much more).

But with federal funding, the desal plant will be turned on full bore. This will free up 100 gigalitres of water from the Murray River allocated to Adelaide for use by farmers upstream in the Murray Darling’s southern basin.

The southern Murray–Darling Basin

The southern Murray–Darling Basin

The federal government expects the water to be used to grow an extra 120,000 tonnes of fodder for livestock. The water will be sold to farmers at a discount rate of A$100 a megalitre. That’s 10 cents per 1,000 litres.

By comparison, the residential price for that water in Adelaide would be A$2.39 to A$3.70 per 1,000 litres.

The production cost of desalinated water is about 95 cents per 1,000 litres when there’s rainwater already stored, according to a cost-benefit study published by the SA Department of Environment and Water in 2016. That means the total cost for the 100 gigalitres will be about A$95 million.

So the federal government is effectively paying A$95 million to sell water for A$10 million: a loss to taxpayers of A$85 million.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

What do we get for the money?

The discounted water provided to individual farmers will be capped at no more than 25 megalitres. The farmers must agree to not sell the water to others and to use it to grow fodder for livestock.

There are many different forms of fodder but livestock producers most favour lucerne hay because it is highly nutritious. But it is also more expensive than cereal, pasture or straw hay.

The amount of hay that can be grown with a megalitre of irrigation water depends on many things, but 120,000 tonnes with 100 gigalitres is possible in the right conditions.

In the Murray-Darling southern basin lucerne hay currently sells for A$450 to A$600 a tonne. That would make the market value of 120,000 tonnes of lucerne A$54 million to A$72 million.

It means, on a best-case scenario, the federal government will be spending A$85 million to subsidise the production of hay worth A$72 million to its producers.

The reality of farming

In practice farms and farmers are incredible diverse, so not all irrigators will necessarily grow lucerne. Alternative fodders such as pasture or cereal hay generally have much lower market values. Which meaning the value of the fodder produced may be much less than the best-case scenario.

It’s worrying that this policy shows such little regard for farming realities. It appears to have been crafted on the premise that every farmer has the same land, the same equipment and the same needs.

Dictating the water must be used for a single purpose runs counter to the needs of the agriculture sector. If farmers could put it to a more effective use, why not allow it?

In addition, it’s not clear how all the monitoring will be done to maintain compliance over such a restrictive regime.

What measures will prevent farmers buying the discounted water and then simply selling an equivalent amount of any carry-over allocation at the going rate of up to $1,000 a megalitre?

How will the government distinguish between the fodder grown with the 25 megalitres provided at low cost and any other fodder harvested on the same farm? How much will it cost to monitor and enforce such arrangements?

The difficulty of answering these types of questions is precisely the reason why countries in the former eastern bloc failed to adequately provide for their populations. Telling people what crop to grow, when to grow, how to water the crop and how it should be consumed has not worked in the past. Farm businesses that respond to prices and use inputs, including water, in a way that suits their long- term commercial needs are generally better off.

It seems a long way from the type of national drought policy Australia needs. It’s hard to see how a policy of this kind does anything other than waste a large amount of public money and disrupt important market mechanisms in agriculture in the process.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox