“Derek’s mother came from the Penfolds family – that’s where he inherited his money,” explains Stephen Whittington, composer and head of Sonic Arts at the University of Adelaide. “He used to drive racing cars, maybe he was a bit of playboy. He was a colourful character.”

Recalling a sort of Adam West-era Bruce Wayne figure without the vigilantism, in the 1950s Jolly poured his money into car racing. Later, he imported a prefabricated Finnish ‘Futuro House’ which for years sat UFO-like on an empty Melbourne Street block. But by the end of the 1960s, his attention and money had turned to the bleeding edge of analogue technology.

“One of his ideas was that he could turn Adelaide into a world centre of advanced recording technology,” Whittington says. By the late 60s Jolly’s music industry exploits had seen him establish Gamba, his North Adelaide studio, and somehow end up with a credit on Johnny Farnham’s 1967 single Sadie (The Cleaning Lady) – for the vacuum cleaner solo. “He thought if he equipped his studio with absolutely the latest technology, it would not only stimulate people here, but musicians would come from all over the world.”

The key, Jolly reckoned, was American inventor Robert Moog, whose early experiments in modular synthesisers gained mainstream attention in 1968 through Wendy Carlos’ bestselling album Switched-On Bach. Soon the Moog was being used by pop acts like The Monkees and Simon and Garfunkel.

“According to what Derek told me, he flew to Trumansburg, New York where Robert Moog was building his synthesisers,” Whittington recalls. “At that stage only a small number of these modular instruments had been constructed. Basically he had to persuade Robert Moog to sell it to him – according to Derek they had a very long evening together drinking rye whiskey, at the end of which Robert Moog said, ‘OK, I’ll sell this to you’.”

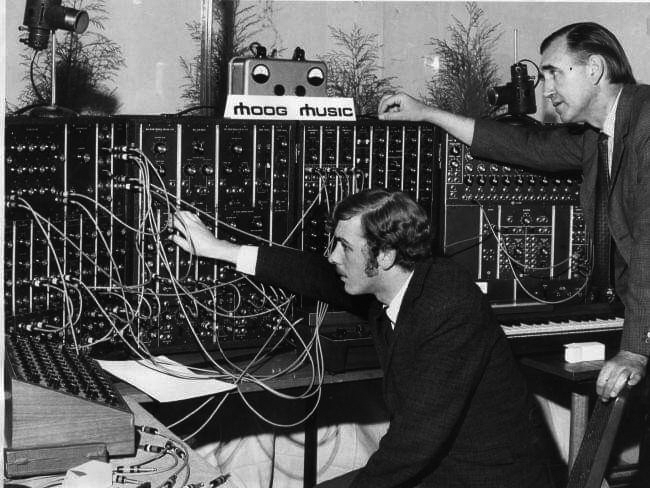

Courtesy of Richard Phillips

Consisting of four units, a keyboard, ribbon controller, elaborate tuning modules and a solid-state sequencer, the Mark III Moog was a complex and expensive piece of technology. “I think the Moog cost US $20,000 at the time, which would have bought you a house, basically. A really good house!”

“I vividly remember the day it arrived in four boxes, it was the first one in the country,” recalls Phil Cuneen, a musician and engineer who worked from Gamba when the Moog arrived. “I unpacked it and Derek said, ‘here, make it work!”

“It was quite a challenge obviously, there was no precedent,” he says of the Moog, which made headlines upon its arrival and later toured the country. “There was a guy from a famous musical family in Adelaide who claims he was the first person to play the Moog,” Cuneen recalls. “I say bullshit – I unpacked the thing!”

After Cuneen, one of the first locals to explore the Moog’s artistic capabilities was Richard Phillips, whose band Travis Wellington Hedge made use of the instrument when recording a cover of The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine-era track Hey Bulldog. “Derek had purchased the Moog synth and offered it to Travis Wellington Hedge for use in recording,” Phillips recalls. “One of his staff setup the synth after quick perusal and that low run up you can hear in the song is the Moog. We all were very happy with, it since we were the first band in the Southern Hemisphere to do a recording using the Moog!”

The Moog’s time at Gamba was short-lived however as few other acts, local or otherwise, quite embraced the instrument’s potential – Cuneen used it primarily for advertising jingles. “We had this amazing tool that could make any sort of sound you could imagine, and of course in the advertising world you had these idiot A&R people asking if you could make it sound like a trumpet,” he says. “Which used to drive me nuts – if you want a bloody trumpet, get a trumpet player!”

Jolly sold the Moog to the University of Adelaide in 1971, where it found a far more appreciative home at its then-emerging electronic music studio, now the Electronic Music Unit (EMU). Established a few years earlier in 1962, for the unit the Moog represented an exciting new frontier. “Prior to the Moog, electronic music relied on tape manipulation in the musique concrète style of cutting, splicing and reversing,” Whittington says.

For years the Moog inspired experimentation among EMU students from its studio beneath Elder Hall. “There would be a concert upstairs, and then at some very quiet moment you might hear some ugly electronic noise coming up through the floor,” he says.

Stephen Whittington and the Moog at the University of Adelaide

Stephen Whittington and the Moog at the University of Adelaide

Today, the Moog doesn’t get out much. Digital technology and emulator software has made its cumbersome modules redundant, but the sounds and innovation it inspired have fundamentally changed the way music is made and appreciated.

“We’re taking about an era where electronic music was very new and very exciting,” Whittington reflects. “Karlheinz Stockhausen came to Adelaide to do a lecture and demonstration in Elder Hall, which was not only sold out but there were hundreds of people queued right out to North Terrace trying to get in to hear this weird German guy talking about electronic music. You can’t imagine that today.”

Much of Jolly’s fortune disappeared in the Black Monday stock market crash of 1987, but he continued to support the arts up until his death in 2002. Whittington cautiously offers one more story, this one secondhand, which in the context of Jolly’s various other endeavours sounds almost plausible.

“He [supposedly] persuaded John Lennon and Paul McCartney to come to Adelaide to see the studio,” he says, stressing the story’s likely apocryphal nature. The sounds of the Moog would later be heard on The Beatles’ 1969 swansong Abbey Road – George Harrison had bought a Moog III of his own. “They came here basically incognito, if that’s possible for them to do that, on a privately-chartered plane.”

“Nah that sounds like bullshit to me,” Cuneen laughs. “Something like that wouldn’t have slipped by me. A total fabrication!”

Music it seems, isn’t the only bit of synthesising Jolly inspired in his lifetime.

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox