Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this story contains images of people who have died

“Stories have always been important, ever since I came back to family,” Archie Roach tells The Adelaide Review. “The old people would sit down and you’d listen to what they told you about mission days, and when they were young, how they coped on the mission, then leaving and coming to the city. It was always rich in storytelling.”

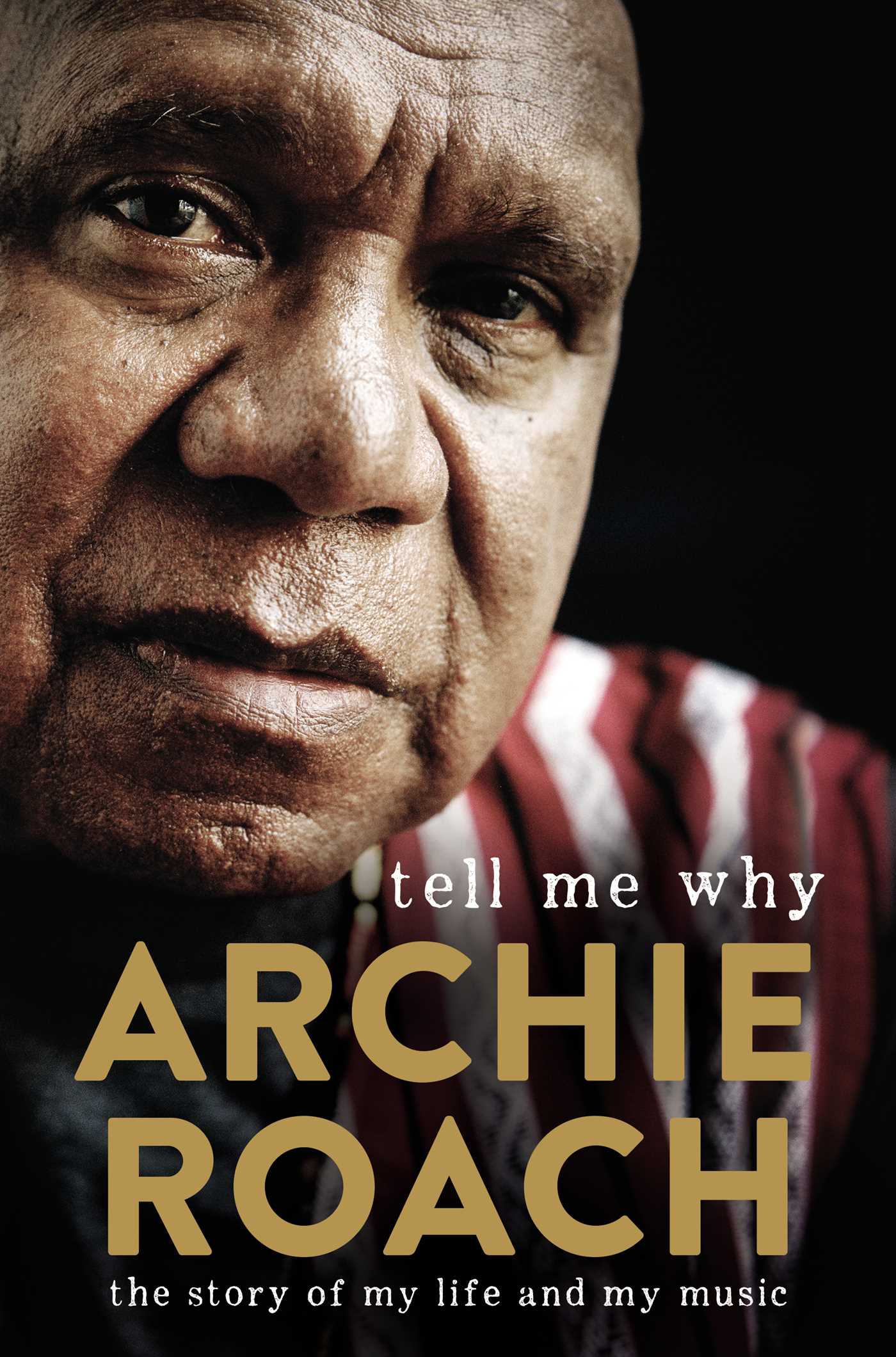

Anyone who has attended an Archie Roach concert knows the stories and anecdotes that bookend his songs are almost as memorable as the melodies. In Tell Me Why, Roach reaches deeper into his past than he ever has onstage.

The book follows Roach’s own story, beginning with a letter he received in 1970 from a scarcely remembered sister named Myrtle, informing young Archie that their mother had died. This short note brought into focus an explosive truth: his life as ‘Archie Cox’, with his beloved adoptive parents Alex and Dulcie, was built on a fiction. The subsequent chapters follow a decades-long search for answers, beginning in Melbourne and Sydney where a teenage Archie sought community and family in parks, pubs and empty houses.

“It was beautiful, what we had in the park – you know, if

we had that without the drinking,” he recalls. “You’d sit around, pass a drink

around and tell stories. I found out who my family was; it’s almost like we had

that connection, that closeness, and it was a community. A lot of those fellas

have passed away, but I remember them fondly, and the things we used to do and

say. Drinking became a problem but it was more than just drinking: it was

dialogue, and conversation.”

Roach as a boy

Roach as a boy

Tell Me Why

Tell Me Why

Tell Me Why does

not shy away from the illness and pain that alcoholism later invited, but Roach

eloquently conveys how having a “charge” offered a means of coping in an often

hostile country, a way to feel “carefree and happy” even as he and his

surrogate family of dislocated Aboriginal men and women felt “part of an

obliterated culture, just intact enough to know it exists but so broken we

didn’t think we could ever be put together again”.

That

life led him to Dunstan-era Adelaide, with money in his pocket from a stint

picking fruit in Mildura, and another life-altering moment ahead of him. First,

he met his future partner and collaborator, the late Ruby Hunter, in the

Salvation Army People’s Palace on Pirie Street. Then, while spending time with

her family and community, he began to learn more about her Ngarrindjeri

heritage, and a connection to culture and country that he had never known.

Suddenly, that difficult-to-define void began to take shape.

“We

didn’t talk much about those things in Melbourne or Fitzroy – whether you’re

Ngarrindjeri, or Gunditjmara, nobody talked like that. When I got to Adelaide

and met Ruby, there was a sense of knowing exactly who they were as a people;

who they were and where they were from, and how they connected to country and

their people through that word – Ngarrindjeri. It certainly changed my outlook,

and got me questioning and searching about my own cultural roots.

“Melbourne’s not far from Adelaide, but it was amazing just that short distance away how different things were,” he says. “We sat in parks and drank and yarned and sang songs and got up to all sorts of things we always do around the country, but in Fitzroy we never talked about country and people in the sense that ‘this is who I

am, this is where I’m from’.”

Ruby Hunter and Roach on tour in London

Ruby Hunter and Roach on tour in London

Throughout the book, Roach’s

perspective broadens as it becomes clear that his own story is not unique.

Hunter too was taken from her family near Lake Alexandrina, as were more and

more people he encountered. Years later, a performance of his now-signature

song Took The Children Away at a 1988 bicentennial protest brought a raucous crowd from

all around the country to a standstill: it was their experience too.

“In

those days you had no idea when you’re just trying to find your family that

it happened across the length and breadth of Australia with Aboriginal

children,” he reflects. “You just thought it maybe only happened to myself for

whatever reason. That was a revelation for me, when older people than me came

up and said, ‘I was taken when I was a boy, and I just met my sister the other

day’. I’m talking about 70-year-old men and women finding themselves after all

those years.”

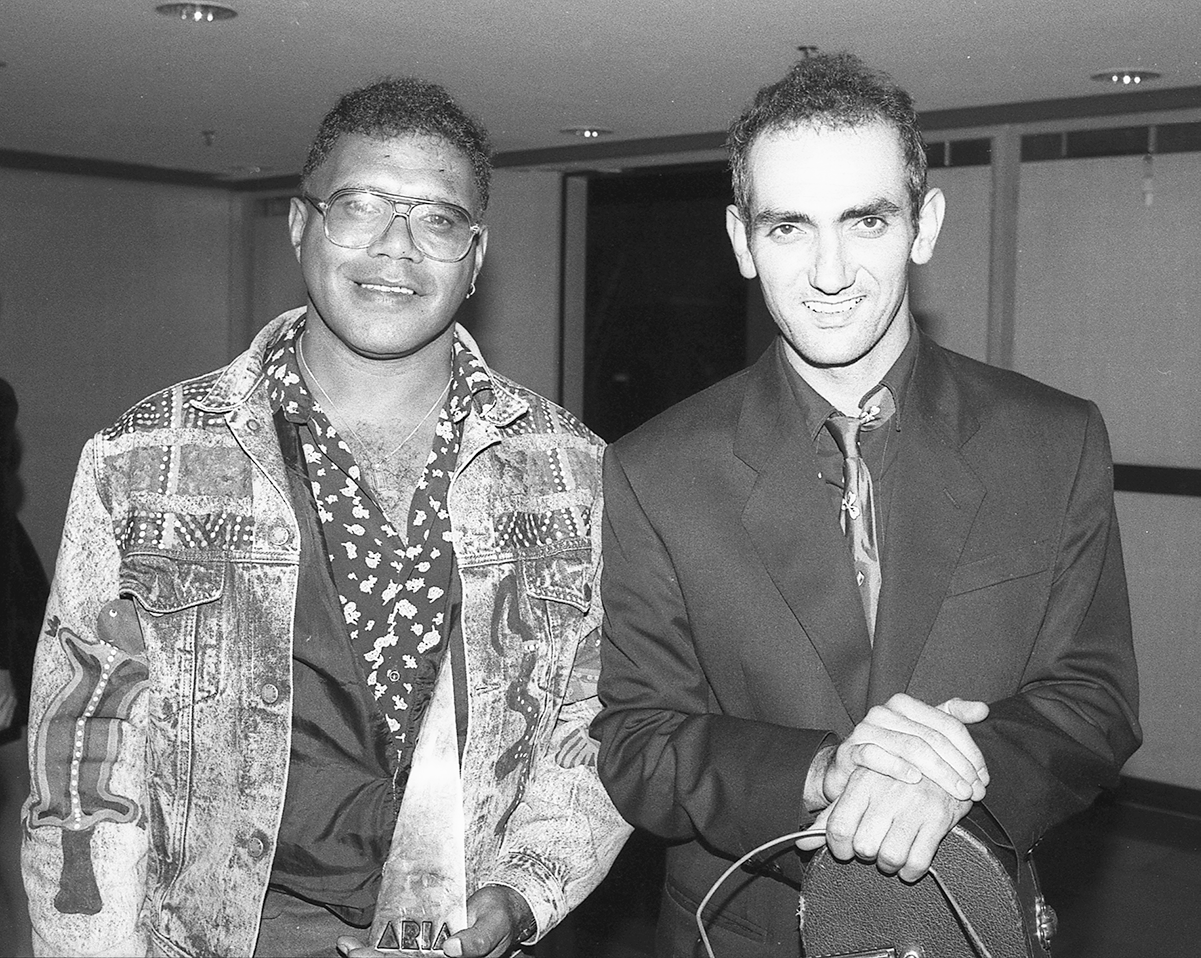

As

Roach’s career takes off in the early 90s following his Paul Kelly-produced

debut album Charcoal Lane, we follow his and Hunter’s artistic journeys

on albums like Looking For Butter Boy and Sensual Being. But

touring around Australia and the world also prompts Roach to further appreciate

the universality of his experience, from meeting First Nations elders in Canada

who found comfort in Took The Children Away, to taking a moment on tour

in Glasgow to look over the River Clyde and reflect upon his Scottish adoptive

father’s own yearning for home.

Roach and Paul Kelly at the 1990 ARIAs

Roach and Paul Kelly at the 1990 ARIAs

Tell Me Why is

at times heartbreaking to read. Roach’s loved ones often die too early, or in

custody, or without answers, and those that survive live with the scars of

cultural erasure, of intergenerational trauma. But Tell My Why is not a

sad book. Every few lines the reader is struck by his good humour, and a deep well

of empathy and forgiveness, both for people like the Coxes who were unwitting

parts of a racist system, and those like himself, who spend a lifetime seeking

answers because of it.

Tell Me Why contains

decades’ worth of answers. But although the book concludes, one suspects Roach

will continue searching – probably with a guitar nearby and an audience to talk

to.

“I’ve

realised that a lot of people in the audience, people who come and see me play

and listen to my stories are much more than an audience,” he reflects. “There’s

an interaction, a connection between me and them. It’s a beautiful connection.”

Tell Me Why, published by Simon & Schuster, is out November 1

Archie Roach will launch Tell Me Why at Nexus Arts on Monday 4 November

Monday 4 November

An Evening with Archie Roach

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox