Whether it’s a pair of seven year old violinists squeaking through Silent Night, teenage boys strumming Jason Mraz covers or longtime favourites drawing a crowd, Adelaide has no shortage of buskers. Half a century ago, the streetscape was not so different. Often driven to music by sheer economic circumstance, these forgotten street performers were the bane of traders and authorities, but won the public’s favour as they earnt a crust with a tune and a smile.

Whether it’s a pair of seven year old violinists squeaking through Silent Night, teenage boys strumming Jason Mraz covers or longtime favourites drawing a crowd, Adelaide has no shortage of buskers. Half a century ago, the streetscape was not so different. Often driven to music by sheer economic circumstance, these forgotten street performers were the bane of traders and authorities, but won the public’s favour as they earnt a crust with a tune and a smile.

Colin G. West, courtesy Gay O'Neill

One of the earliest names to win a degree of notoriety and public affection was Patrick ‘Patsy’ Weldon, who for many years played a hand cranked organ, despite suffering from a limb deformity. By 1915 his instrument was said to have “lost half of its teeth and omitted 50 percentum of the notes”, but Weldon defiantly rejected any offers to replace it. “Those notes that won’t go are worth more cash than the others that do,” he reportedly said. “They cause people to pity me for being too poor to have a new organ, and so they give me more money.” While details on Weldon’s life are scant, it seems he met a quiet end at Parkside Mental Hospital, where he was last seen by a reporter in 1918.

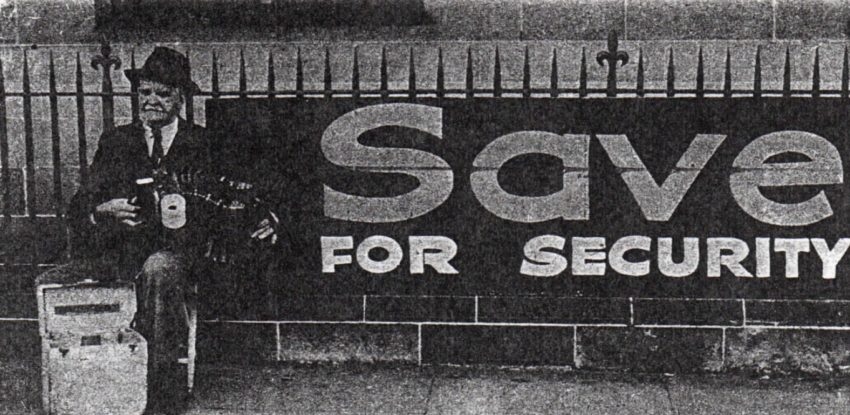

Perhaps the best known and longest-running busker of the early 20th century however was Percy Lines, who spent 45 years busking in the same King William Street spot. Blinded at 28 in a Broken Hill mining accident, by 1911 Percy had picked up the accordion and taken to the streets to support his wife and children. Lin es was circumspect about the hand life had dealt him. “Blindness is my lot,” he once said. “I don’t like it but I do try to reconcile myself to it … I have learned to put up with myself, and like it. Life has been worth living after all.”

Percy Lines

Percy Lines

But his path to becoming a beloved local icon wasn’t always smooth. Early in his busking career, Lines walked into the offices of the Daily Herald to register his frustration at recent moves to outlaw blind people from earning money on the street, arguing that the pension could not support his large family, nor should he have to forego his financial independence when he could just as easily earn his own money. Something, he said, that Salvation Army bands and other non-blind performers did without issue.

Around the same time, ‘Piccolo Pete’ captured the public’s imagination despite his apparent musical limitations on the tin whistle. “People have often wondered who I am, and what I am,” Pete told The Truth in July 1946. Rarely speaking to passers-by, rumours of his true origins flourished. Some speculated that he was a wealthy, educated man with years of musical tuition; others spun tales of a failed love affair that drove him to his tinny vocation.

The true story of the man born Francis Roland Bee was much humbler. “The housing shortage and lack of accommodation struck me like hundreds of others,” he said in the same interview, published soon after his arrest for sleeping rough on the grounds of the School of Mines (now part of UniSA’s City East campus). “But the Adelaide people have been good enough to have kept me off the dole for the last 15 years. There is no big money in doing the work I do; I work long hours for a few odd shillings, but I like the outdoor life and at 59 years of age I have little to live for,” he said. Indeed, ‘Pete’ would pass away just weeks later, having been hospitalised for the second time that year.

Attempts to reign in street performers were frequent. In October 1931 the City of Adelaide, supported by city traders, passed a bylaw to regulate street performance via a permit system. Complaints continued however, with one Rundle Street trader “enduring” a brass band in front of his building. The new system mandated performers maintain a respectable appearance, move on when asked by a nearby resident and only perform for 15 minutes at a time within a 100 yard radius.

State Library of South Australia, B35394

State Library of South Australia, B35394 If required, musicians could also be compelled to audition in an ante-room in the Town Hall. According to The Advertiser, singers were the subject of a blanket ban – they were deemed to make “too much noise”. ‘Piccolo Pete’ was frequently in trouble for playing, fined £1, 2s January 1933 for refusing to move on after being ordered to move by police, despite having a permit. He told the court that the police “regarded street musicians as vagrants, which was wrong.”

Despite such attitudes, the presence of street performers continued unabated, becoming an important part of Adelaide’s fabric. “People say that we look able-bodied and healthy, but you can bet we would not be doing this if there were other jobs,” an anonymous performer told The Mail at the time of the bylaws. “It is hateful. But we have others to think of beside ourselves”.

Unearth more hidden stories from the past, present and future of Adelaide’s music scene in ‘City Of Music’, part of the new Adelaide Tours guided walks program.

Detours is presented in partnership with National Trust South Australia and The Adelaide Review

Detours is presented in partnership with National Trust South Australia and The Adelaide Review

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox